Social media shows stunning sunset campsite photos, but the spreadsheets tell a different story. Full-time RV living in 2025 costs between $2,500 and $5,000 monthly—and that figure hides a capital investment trap that catches most aspiring full-timers off guard.

I analyze North American RV market trends by cross-referencing industry reports from the RV Industry Association, KOA’s camping studies, and government housing data with qualitative insights from thousands of active full-timers in communities like r/GoRVing, the Escapees RV Club forums, and iRV2.com.

This combination reveals what the statistics alone miss: insurance jumped 22% nationally but regional variations push Alberta and Florida full-timers 30-40% higher. “Free” boondocking actually requires $5,000-20,000 upfront. And the depreciation trap works differently than your financial planner expects.

The economics have fundamentally shifted since 2020. Understanding whether RV living saves money versus traditional housing requires looking past both the Instagram lifestyle marketing and the doom-and-gloom cost calculators to examine the actual financial mechanisms at work.

I built a custom GPT to help you do just that. It uses real-world data from 2020–2025 to analyze full-time RV costs, boondocking tradeoffs, and how it all stacks up against traditional housing.👉 Try the Full-Time RV Cost Analyst GPT

RV living costs have climbed across every category since 2020

Insurance premiums for full-time RVers increased 22% nationally in 2024 compared to 2023, while campground industry revenue grew at 8.3% annually since 2020.[1][2] Fuel, maintenance, and storage costs followed similar trajectories. The pandemic-era RV boom created demand pressures that persisted even as shipment volumes corrected downward by 40% from their 2021 peak.

The 22% insurance figure tells only part of the story. Regional risk factors create dramatic variations—full-timers in hurricane-prone Florida and hail-prone Alberta report increases of 30-40% when seeking quotes, significantly above the national average. One member of the Escapees RV Club forum documented receiving quotes from five carriers—three declined coverage outright for summer stays in high-risk areas, while the two willing insurers charged premiums 35% higher than comparable policies in lower-risk regions. This regional variation rarely appears in generic cost analyses that rely on national averages.

Campground fees climbed alongside insurance costs. KOA, North America’s largest private campground chain, now charges $40-80 per night depending on location and season, with Colorado locations averaging $59 nightly and premium tourist destinations hitting $100-200 per night.[1] Parks Canada implemented a 4.1% fee increase in January 2024, with typical campgrounds ranging $40-75 CAD nightly.[3] Monthly rates offer better value at $500-1,000, but availability has become the constraint rather than price. The Dyrt’s 2025 camping report found that 56.1% of campers struggled to find available campsites in 2024, up from 45.5% reporting sold-out conditions in 2023.[4]

This scarcity gives campground operators continued pricing power. While the percentage of campgrounds raising rates fell from 45.3% in 2023 to 38.9% in 2024, those that did increase prices cited inflation as the primary driver.[4] Over one-third of properties planned additional rate increases for 2025. Operators point to rising property taxes, utilities, insurance premiums, employee wages, and capital investments in pools, spas, and glamping amenities as cost pressures they must pass along.

Maintenance represents another category where national averages mask individual volatility. Experts recommend annual budgets of $1,500-5,000 or 10-15% of the RV’s purchase price.[5] RV shop labor rates typically hit $120+ per hour, higher than automotive mechanics, because technicians need expertise spanning plumbing, electrical, HVAC, appliances, and construction. Major repairs are particularly punishing: roof replacements run $7,000-10,000, slide-out mechanism repairs cost $2,500-9,000, and engine overhauls can exceed $10,000.[6] One full-timer documented spending $4,000+ in first-year maintenance on a 2017 Forest River Georgetown, while another owner’s extended warranty offset $5,721 in repairs that would have totaled $17,981 without coverage.[7]

Fuel costs provided the one category where prices improved rather than worsened. After spiking to $3.61 per gallon in April 2024, U.S. gasoline averaged $3.15 per gallon in May 2025—down 12.6% year-over-year.[8] Diesel followed a similar trajectory at $3.50 per gallon, down 8.5% from the previous year. For Class A motorhomes getting 6-10 MPG and Class C units averaging 8-14 MPG, this matters: a 1,000-mile trip in a Class A costs roughly $390 in fuel at current prices, consuming $300-700 monthly for typical travel patterns.

The cumulative effect of these increases transformed the economics of full-time RV living. Campground industry revenue reached $10.9 billion in 2025, reflecting the 8.3% compound annual growth rate that has held steady since 2020.[1] The RV Industry Association’s data shows recreational RV ownership declined from 11.2 million households in 2021-2022 to 8.1 million in 2025, yet paradoxically the number of full-time RV dwellers kept climbing.[9] This suggests two distinct markets: recreational owners exiting after pandemic enthusiasm waned, and necessity-driven full-timers entering despite rising costs.

Purchase prices remain elevated despite market correction

RV manufacturers expect another 8-10% price increase in June 2025 despite shipments falling to 356,518 units in 2024, down 6.9% year-over-year.[9] Prices haven’t returned to pre-pandemic levels because the cost structure itself changed—lumber, aluminum, chassis, and electronics all remain significantly above 2019 baselines, while skilled labor shortages keep wages elevated.

The manufacturing cost reality explains why waiting for prices to drop has proven futile. Lumber, which spiked dramatically during the pandemic, has not returned to earlier lows and remains a significant cost driver for RV frames and interiors.[10] Steel and aluminum prices have stayed well above pre-pandemic levels despite some correction from 2021 peaks. Chassis and frame costs increased due to global metal demand, continued tariffs, and supply constraints that manufacturers cannot easily circumvent.

Technology expectations added another cost layer. Wi-Fi boosters, smart appliances, safety systems, backup cameras, and entertainment systems are increasingly standard features rather than premium add-ons. This drives up electronic component costs by an estimated 15-20% compared to pre-pandemic models.[10] Labor shortages in skilled trades—welding, electrical work, plumbing—forced manufacturers to pay higher wages to attract workers, while supply bottlenecks for specialty parts and imported goods continue to add costs and delays even in 2025.

Used RV prices softened from their pandemic peaks but remain elevated. Motorhomes at auction now average $60,607, according to industry tracking data. Dealers are offering 20-30% discounts off manufacturer’s suggested retail prices to move inventory, but this creates misleading optics. A 30% discount off an inflated 2024 MSRP often still exceeds what the same model commanded in 2019. The dealers aren’t being generous—they’re working through expensive inventory purchased during the boom years at prices that today’s buyers resist paying in full.

RV shipments surged 40% from 2020 to 2021, reaching a record 600,000 units, with first-time buyers accounting for 50-80% of purchases.[11] This created a pipeline of high-priced inventory that took years to clear. Manufacturers reduced production in 2023 and 2024 to avoid oversupply, which prevented prices from collapsing but also meant fewer discounted units for buyers hoping to time the market.

Financing costs compounded the sticker price challenge. Interest rates remain significantly higher than the ultra-low rates of the late 2010s. Even as inflation cooled, RV buyers in 2025 must finance at rates of 5-8%, raising monthly payments substantially.[10] A $60,000 RV financed at 7% over 15 years costs $539 monthly just in principal and interest, before insurance, maintenance, or operational expenses. That same RV financed at 3% in 2019 would have cost $415 monthly—a $124 difference driven entirely by interest rate environment.

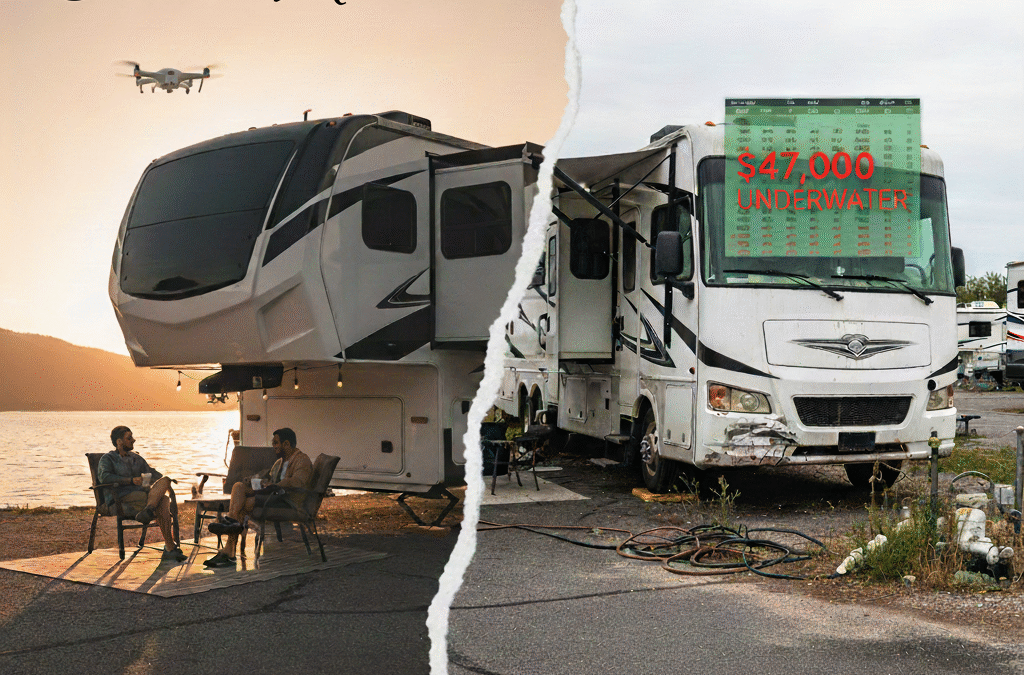

The depreciation curve makes financing particularly punishing. RVs depreciate 30-50% in the first five years, unlike homes that typically appreciate. Someone financing a $60,000 RV discovers after three years they owe $40,000 but the RV is worth only $35,000-40,000. They’re underwater, paying interest on a rapidly depreciating asset. This creates a trap: they cannot sell without bringing cash to closing, yet continuing to pay compounds the wealth destruction as depreciation continues.

Industry analysts at Morton on the Move noted in their 2025 buying guide that new RV prices “haven’t plummeted to pre-pandemic levels” and dealers are still working through expensive inventory.[12] Used RV prices have softened, but many pandemic-era buyers are holding onto their rigs rather than selling at losses, which keeps used inventory tight and prices elevated. The correction everyone predicted never fully materialized because the cost inputs—materials, labor, financing—didn’t correct proportionally.

Boondocking networks expanded—but “free” camping requires major capital investment

Harvest Hosts grew from 600 locations in 2018 to over 5,000 in 2025, while Boondockers Welcome added 3,500+ private properties—creating legitimate free camping infrastructure.[13][14] But accessing this network requires $5,000-20,000 in upfront capital for solar panels, lithium batteries, inverters, and connectivity equipment that generic cost calculators don’t include in “getting started” budgets.

The capital requirement creates a bifurcation in who can actually benefit from the boondocking revolution. Solar power systems capable of running air conditioning, refrigerators, and laptops cost $2,000-15,000 depending on power needs and installation complexity. A basic 400-watt solar array with a single lithium battery and inverter starts around $3,000 for DIY installation. Comprehensive off-grid setups with 800+ watts of solar, multiple lithium batteries, and sufficient inverter capacity to run all systems exceed $10,000 before labor costs.

The connectivity gatekeeper has become more expensive than the power itself. Monitoring discussions in r/vandwellers and iRV2.com reveals that Starlink represents the primary financial blindside for working-age RVers. The $150 monthly subscription plus $599 hardware cost wasn’t in most people’s pre-launch budgets, yet it’s become non-negotiable for remote workers. One thread on iRV2 documented 47 full-timers who abandoned boondocking plans entirely because they couldn’t afford both the solar setup and the Starlink subscription—choosing instead to stay in RV parks with included Wi-Fi despite the $800-1,200 monthly cost.

Cell signal boosters add another $500+ to the connectivity budget. While they don’t replace Starlink for bandwidth-intensive work, they’re essential for maintaining phone service in remote areas where emergency calls or basic communication requires amplification. Water management systems—larger tanks, water bladders for refills, and potentially composting toilets—extend off-grid capability but add $1,000-3,000 to initial costs.

Membership programs themselves carry minimal expense compared to equipment. Harvest Hosts charges $99-179 annually for access to wineries, farms, breweries, and museums offering overnight stays. Boondockers Welcome costs $79 annually for 3,500+ private property hosts, with over 75% offering electric and water hookups. In Canada, Terego lists approximately 1,600 farms, vineyards, and attractions where RVers can overnight with membership.[15] Combined, these networks cost under $300 annually—trivial compared to equipment but only accessible after making the capital investment.

Public land opportunities remain substantial for those equipped to use them. The Bureau of Land Management manages approximately 245 million acres where dispersed camping is generally permitted for up to 14 days within a 28-day period.[16] Long-Term Visitor Areas in Arizona and California allow seven-month stays for $420 in 2025, representing just $60 monthly. In Canada, 89% of land is Crown Land where Canadian residents can camp free for up to 21 days per site annually, though non-residents require permits costing $10.57 per person per night in Ontario.[17]

The savings calculation depends entirely on capital access. Comparing monthly costs reveals why boondockers can maintain this lifestyle despite rising prices. A budget RV park scenario costs $800 monthly rent plus $150 electricity, totaling $950. Boondocking reduces this to $500-600 monthly for a frugal approach, yielding savings of $350-450 monthly or $4,200-5,400 annually. An average RV park at $1,200 monthly versus boondocking at $500-600 creates savings of $600-700 monthly or $7,200-8,400 annually. The membership network approach—combined Harvest Hosts and Boondockers Welcome at $248 annually versus minimum campground rates of $35 nightly—delivers savings exceeding $12,000 annually.

But these savings only materialize after spending $5,000-20,000 upfront plus $150+ monthly for connectivity. This creates a troubling dynamic: boondocking works brilliantly for lifestyle choosers with capital to invest, but remains inaccessible to economic-necessity RVers who lack upfront resources. The boondocking revolution didn’t make RV living cheaper for everyone—it made it cheaper for those who could afford the admission price.

Practical pathways to free camping—and what the resources don’t tell you

The boondocking narrative often conflates two distinct camping styles—true off-grid living with solar and lithium batteries versus basic overnight parking that requires minimal infrastructure. Understanding this distinction reveals accessible entry points that don’t require five-figure investments.

Federal public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Forest Service permit dispersed camping across approximately 245 million acres, typically allowing 14-day stays within 28-day periods.[16] This represents the largest free camping resource in North America, yet it remains underutilized by budget-constrained RVers who assume all boondocking requires expensive solar setups. Many dispersed sites along maintained Forest Service roads work for stock RVs with standard generators, provided you can handle the noise restrictions and propane consumption.

The store parking landscape has fundamentally shifted

The retail parking that sustained budget RVers for decades contracted sharply between 2020 and 2025. Approximately 50% of Walmart locations now prohibit overnight stays, up from 40% in 2023, with restrictions concentrated near tourist destinations and major highways. The iconic big-box overnight stop hasn’t disappeared, but it requires more advance research and fallback planning than it did five years ago.

Cracker Barrel emerges from community reports as the most consistently RV-friendly major retail chain in 2025, with many locations maintaining designated RV spaces and quieter evening environments. However, an unspoken expectation has solidified: patronizing the business isn’t legally required, but managers increasingly view dining as the implicit exchange for parking space. One Tennessee manager framed it directly: “We’re happy to have you stay, but we’re not a campground—we’re a restaurant.” Budget travelers report average costs of $20-30 for two meals when using Cracker Barrel overnight, still cheaper than campgrounds but not truly free.

Truck stops evolved differently, with major chains like Love’s, Pilot Flying J, and TA expanding RV-specific services rather than restricting access. Some Love’s locations now offer dedicated RV lanes with hookups for $15-25 nightly—not free, but providing amenities that justify the cost for travelers who need them. The critical distinction: these paid spots sit alongside traditional free parking areas, giving RVers choices based on their power and water needs rather than forcing an all-or-nothing decision.

Home Depot and Lowe’s parking lots represent an underutilized resource in urban areas where other options disappeared. These locations typically open early for contractors, suggesting a strategy: arrive after 8pm, depart before 6am, and park away from loading zones. Success rates vary significantly by location and local ordinances, requiring the same verification calls that Walmart stays demand.

Free camping apps—which ones actually deliver current information

The explosion of camping apps created a paradox: more information sources but less clarity about which data remains current. Apps aggregate user-submitted content, but update frequency varies wildly. A five-star boondocking spot from 2023 may have closed road access, changed regulations, or become overcrowded without the app reflecting these changes.

FreeCampsites.net maintains the most comprehensive database of no-cost camping locations without requiring membership fees. The trade-off is complete dependence on user contributions—information quality fluctuates based on whether recent visitors submitted updates. Cross-referencing with official Forest Service or BLM websites provides the most reliable verification for free camping locations.

iOverlander excels at GPS coordinates for dispersed sites, with particularly strong coverage in the western states where BLM land dominates. The platform receives 5,000+ place corrections monthly from active users, indicating robust community engagement.[18] However, coordinates for dispersed camping can be off by anywhere from a few feet to a mile depending on how contributors marked locations—treat them as general area guides rather than exact destinations.

Campendium combines free and paid camping information with detailed user reviews that often reveal critical details generic listings miss. Recent reviews matter more than star ratings—a five-star review from three years ago doesn’t account for the road washout last spring or seasonal gate closures. Filtering for reviews posted within 60 days, particularly for dispersed sites on Forest Service roads, provides the most actionable intelligence.

The Dyrt boasts 500,000+ campsites listed with millions of active users, including 16,000+ free dispersed and overnight parking locations. The platform’s strength lies in its extensive database and active community, though like other crowdsourced resources, information currency depends on recent user updates.

Official government resources deserve equal attention as crowdsourced apps. Recreation.gov handles reservations for federal campgrounds, many of which charge fees, but it also shows which National Forest campgrounds operate on first-come, first-served basis without reservation requirements.[19] The USFS Interactive Visitor Map displays dispersed camping areas, forest roads, and current closures with official authority that community apps can’t match.

| Resource | Best Use Case | Key Limitation | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| FreeCampsites.net | Comprehensive free site database | Update frequency varies by location | Free |

| iOverlander | GPS coordinates for dispersed sites | Coordinates may be approximate | Free |

| Campendium | Detailed reviews and site conditions | Mixes free and paid campgrounds | Free |

| AllStays | Walmart/retail parking verification | Requires paid app for full features | $10-15 one-time |

| Recreation.gov | Official federal campground data | Primarily covers fee campgrounds | Free to search |

Regional strategies for finding free camping without solar investment

Free camping accessibility varies dramatically by region, with western states offering substantially more options than eastern locations due to federal land management patterns. Understanding regional characteristics helps target searches toward realistic options rather than chasing theoretical opportunities that don’t exist in your area.

Desert Southwest (Arizona, California, New Mexico): Quartzsite, Arizona represents perhaps the most accessible entry point to free camping culture, with thousands of RVers congregating on BLM land from October through March. The Long Term Visitor Areas charge $420 for seven-month stays—just $60 monthly—providing legal camping with minimal amenities and a built-in community of fellow full-timers.[16] Anza-Borrego Desert State Park in California allows permit-free primitive camping year-round, one of the only California state parks with this distinction.

Mountain West (Colorado, Utah, Idaho): National forests blanket these states with dispersed camping along countless forest service roads. San Juan National Forest near Durango, Coconino National Forest outside Flagstaff, and Caribou-Targhee on the Idaho-Wyoming border all provide extensive free camping during summer months. The critical limitation: seasonal accessibility. Snow closes most high-elevation forest roads from October through May, concentrating free camping into a compressed 5-6 month window that creates competition for desirable spots.

Great Plains (South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming): Buffalo Gap National Grassland in South Dakota offers sweeping prairie camping with dramatic badlands overlooks. These areas see less traffic than mountain forests because they lack the Instagram-worthy scenery, but they provide reliable free camping with easier road access suitable for larger RVs. Wind represents the primary challenge rather than terrain.

Northeast (Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine): Free camping options contract significantly east of the Mississippi. State forests in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine permit primitive camping, but typically require advance permission from forest headquarters rather than allowing spontaneous dispersed camping. Crown Land camping in Canada provides free options for Canadian residents (21 days per site annually), but non-residents face per-night fees that eliminate the cost advantage.[17]

The verification process that prevents wasted trips

Successful free camping depends less on which app you use than on your verification habits before departing. Cross-referencing multiple sources and confirming current conditions through direct contact separates productive trips from frustrating wild goose chases.

The three-source rule provides reliable verification: if a site appears on a crowdsourced app with recent positive reviews, shows up on official Forest Service or BLM maps, and a ranger station confirms access when called, you can reasonably trust it exists and remains accessible. When only one source mentions a site—especially for dispersed camping—treat it as unverified until you find corroborating information. Twenty minutes of verification prevents two-hour drives to locked gates or non-existent turnoffs.

Seasonal considerations affect northeastern and mountain camping significantly. Apps rarely update for mud season closures, hunting season restrictions, or winter gate closures that make previously accessible sites unavailable. A five-minute phone call to the relevant ranger district confirms whether gates are open and sites are accessible before you drive hours into the mountains. USFS Ranger District contact information remains available online for all national forests.

Recent reviews trump aggregate ratings. Filter specifically for reviews posted within 60 days when evaluating dispersed sites. Spring flooding washes out roads, summer fires trigger closures, and fall hunting seasons create temporary restrictions that older reviews can’t reflect. One Escapees RV Club member documented spending four hours driving forest roads to three different “highly rated” sites, only to find all three inaccessible due to recent damage. Better advance verification would have saved the entire day.

Starting without solar—the generator-based approach

The solar-or-nothing framing misrepresents how many RVers actually approach free camping. Generator-based camping at dispersed sites provides a viable entry point that requires no capital investment beyond what most RVs already carry. The trade-offs involve noise, propane consumption, and generator hours limits at some locations, but these constraints don’t prevent access to free camping entirely.

Most dispersed camping areas on federal land permit generator use during daytime hours (typically 8am-8pm), with quiet hours enforced overnight. A standard 3,000-watt generator running 4-6 hours daily provides sufficient power to charge batteries, run refrigerators, and operate basic systems without solar panels. Propane consumption increases significantly—budget an additional 10-15 gallons weekly compared to hookup camping—but this remains substantially cheaper than nightly campground fees.

The progressive investment approach allows building off-grid capability gradually. Start with generator-based free camping to prove the concept works for your travel style and identify which systems matter most. Many RVers discover they need less power than anticipated, or that their usage patterns don’t justify comprehensive solar installations. Others confirm that off-grid camping suits them and invest in solar systematically—400 watts this year, additional batteries next year—rather than attempting to build the complete system upfront.

This staged approach also reveals whether boondocking actually saves money in your specific situation. If you’re traveling extensively and burning fuel to reach remote free sites, the savings over staying stationary at a monthly RV park diminish. If you find you can’t tolerate generator noise or prefer campground amenities, the solar investment becomes a poor use of limited capital. Better to discover these preferences with minimal investment than after spending $15,000 on equipment you ultimately don’t use.

Free camping apps—which ones actually deliver current information

The explosion of camping apps created a paradox: more information sources but less clarity about which data remains current. Apps aggregate user-submitted content, but update frequency varies wildly. A five-star boondocking spot from 2023 may have closed road access, changed regulations, or become overcrowded without the app reflecting these changes.

FreeCampsites.net maintains the most comprehensive database of no-cost camping locations without requiring membership fees. The trade-off is complete dependence on user contributions—information quality fluctuates based on whether recent visitors submitted updates. Cross-referencing with official Forest Service or BLM websites provides the most reliable verification for free camping locations.

iOverlander excels at GPS coordinates for dispersed sites, with particularly strong coverage in the western states where BLM land dominates. The platform receives 5,000+ place corrections monthly from active users, indicating robust community engagement.[18] However, coordinates for dispersed camping can be off by anywhere from a few feet to a mile depending on how contributors marked locations—treat them as general area guides rather than exact destinations.

Campendium combines free and paid camping information with detailed user reviews that often reveal critical details generic listings miss. Recent reviews matter more than star ratings—a five-star review from three years ago doesn’t account for the road washout last spring or seasonal gate closures. Filtering for reviews posted within 60 days, particularly for dispersed sites on Forest Service roads, provides the most actionable intelligence.

Official government resources deserve equal attention as crowdsourced apps. Recreation.gov handles reservations for federal campgrounds, many of which charge fees, but it also shows which National Forest campgrounds operate on first-come, first-served basis without reservation requirements.[19] The USFS Interactive Visitor Map displays dispersed camping areas, forest roads, and current closures with official authority that community apps can’t match.

| Resource | Best Use Case | Key Limitation | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| FreeCampsites.net | Comprehensive free site database | Update frequency varies by location | Free |

| iOverlander | GPS coordinates for dispersed sites | Coordinates may be approximate | Free |

| Campendium | Detailed reviews and site conditions | Mixes free and paid campgrounds | Free |

| AllStays | Walmart/retail parking verification | Requires paid app for full features | $10-15 one-time |

| Recreation.gov | Official federal campground data | Primarily covers fee campgrounds | Free to search |

Regional strategies for finding free camping without solar investment

Free camping accessibility varies dramatically by region, with western states offering substantially more options than eastern locations due to federal land management patterns. Understanding regional characteristics helps target searches toward realistic options rather than chasing theoretical opportunities that don’t exist in your area.

Desert Southwest (Arizona, California, New Mexico): Quartzsite, Arizona represents perhaps the most accessible entry point to free camping culture, with thousands of RVers congregating on BLM land from October through March. The Long Term Visitor Areas charge $420 for seven-month stays—just $60 monthly—providing legal camping with minimal amenities and a built-in community of fellow full-timers.[16] Anza-Borrego Desert State Park in California allows permit-free primitive camping year-round, one of the only California state parks with this distinction.

Mountain West (Colorado, Utah, Idaho): National forests blanket these states with dispersed camping along countless forest service roads. San Juan National Forest near Durango, Coconino National Forest outside Flagstaff, and Caribou-Targhee on the Idaho-Wyoming border all provide extensive free camping during summer months. The critical limitation: seasonal accessibility. Snow closes most high-elevation forest roads from October through May, concentrating free camping into a compressed 5-6 month window that creates competition for desirable spots.

Great Plains (South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming): Buffalo Gap National Grassland in South Dakota offers sweeping prairie camping with dramatic badlands overlooks. These areas see less traffic than mountain forests because they lack the Instagram-worthy scenery, but they provide reliable free camping with easier road access suitable for larger RVs. Wind represents the primary challenge rather than terrain.

Northeast (Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine): Free camping options contract significantly east of the Mississippi. State forests in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine permit primitive camping, but typically require advance permission from forest headquarters rather than allowing spontaneous dispersed camping. Crown Land camping in Canada provides free options for Canadian residents (21 days per site annually), but non-residents face per-night fees that eliminate the cost advantage.[17]

The verification process that prevents wasted trips

Successful free camping depends less on which app you use than on your verification habits before departing. Cross-referencing multiple sources and confirming current conditions through direct contact separates productive trips from frustrating wild goose chases.

The three-source rule provides reliable verification: if a site appears on a crowdsourced app with recent positive reviews, shows up on official Forest Service or BLM maps, and a ranger station confirms access when called, you can reasonably trust it exists and remains accessible. When only one source mentions a site—especially for dispersed camping—treat it as unverified until you find corroborating information. Twenty minutes of verification prevents two-hour drives to locked gates or non-existent turnoffs.

Seasonal considerations affect northeastern and mountain camping significantly. Apps rarely update for mud season closures, hunting season restrictions, or winter gate closures that make previously accessible sites unavailable. A five-minute phone call to the relevant ranger district confirms whether gates are open and sites are accessible before you drive hours into the mountains. USFS Ranger District contact information remains available online for all national forests.

Recent reviews trump aggregate ratings. Filter specifically for reviews posted within 60 days when evaluating dispersed sites. Spring flooding washes out roads, summer fires trigger closures, and fall hunting seasons create temporary restrictions that older reviews can’t reflect. One Escapees RV Club member documented spending four hours driving forest roads to three different “highly rated” sites, only to find all three inaccessible due to recent damage. Better advance verification would have saved the entire day.

Starting without solar—the generator-based approach

The solar-or-nothing framing misrepresents how many RVers actually approach free camping. Generator-based camping at dispersed sites provides a viable entry point that requires no capital investment beyond what most RVs already carry. The trade-offs involve noise, propane consumption, and generator hours limits at some locations, but these constraints don’t prevent access to free camping entirely.

Most dispersed camping areas on federal land permit generator use during daytime hours (typically 8am-8pm), with quiet hours enforced overnight. A standard 3,000-watt generator running 4-6 hours daily provides sufficient power to charge batteries, run refrigerators, and operate basic systems without solar panels. Propane consumption increases significantly—budget an additional 10-15 gallons weekly compared to hookup camping—but this remains substantially cheaper than nightly campground fees.

The progressive investment approach allows building off-grid capability gradually. Start with generator-based free camping to prove the concept works for your travel style and identify which systems matter most. Many RVers discover they need less power than anticipated, or that their usage patterns don’t justify comprehensive solar installations. Others confirm that off-grid camping suits them and invest in solar systematically—400 watts this year, additional batteries next year—rather than attempting to build the complete system upfront.

This staged approach also reveals whether boondocking actually saves money in your specific situation. If you’re traveling extensively and burning fuel to reach remote free sites, the savings over staying stationary at a monthly RV park diminish. If you find you can’t tolerate generator noise or prefer campground amenities, the solar investment becomes a poor use of limited capital. Better to discover these preferences with minimal investment than after spending $15,000 on equipment you ultimately don’t use.

Campground scarcity creates booking strategies the data doesn’t capture

The 56.1% booking difficulty statistic[4] doesn’t reveal the actual mechanism frustrating full-timers: reservation sniping by bots and insiders at national parks. Successful bookers in the Escapees forum no longer prioritize early reservations—they book “shoulder days” (Monday-Wednesday slots) to stay in the system for weekend cancellations that open predictably.

This tactical shift emerged from community problem-solving rather than official guidance. Recreation.gov opens reservation windows six months in advance at 10am Eastern Time for most federal campgrounds.[19] Prime weekend spots at popular destinations like Yosemite, Yellowstone, or Acadia disappear within seconds. Early attempts to simply “book faster” failed because automated bots and reservation services working for unofficial resellers grabbed spots before human users could complete checkout.

The shoulder-day strategy exploits how the cancellation system actually works. RVers discovered that weekend cancellations open most frequently within 48-hour windows as weather forecasts finalize or work schedules change. But you can only see and claim cancellations if you already have a reservation at that campground. By booking less-desirable Monday-Wednesday slots that others avoid, you gain system access to monitor for Thursday-Sunday cancellations. One Escapees forum member documented booking 23 national park stays in a single season using this method, paying weekday rates for half her nights while accessing prime weekend slots through cancellation monitoring.

Dynamic pricing models at private campgrounds added another layer of complexity. Weekday rates run $35-50, weekend rates jump to $70-100+, and holiday weekends can hit $150-200 at premium locations. This pricing spread incentivizes the shoulder-day approach even at private parks—book cheap weekdays, enjoy the facilities, then extend through weekends when spots open.

The booking difficulty statistics also mask regional variation. Western parks face more intense competition than Midwest or Southern locations. Coastal areas see summer pressure while desert parks struggle with winter demand. A full-timer traveling year-round learns to “follow the empty campgrounds”—visiting popular destinations during shoulder seasons when both availability and pricing improve dramatically.

Despite these workarounds, the scarcity persists. While the percentage of campgrounds raising rates fell from 45.3% in 2023 to 38.9% in 2024, over one-third of properties planned additional 2025 increases.[4] Inflation remains the primary driver operators cite, but the continued rate growth despite falling demand from recreational RVers—ownership dropped from 11.2 million to 8.1 million households—suggests pricing power from full-timer demand rather than temporary pandemic enthusiasm.

New campground construction hasn’t kept pace with demand. While glamping facilities and upscale RV resorts proliferated, basic campgrounds with standard hookups saw limited expansion. The capital cost of land acquisition, utility installation, environmental compliance, and local zoning approvals creates barriers that prevent rapid supply response even when demand signals are clear.

Competition intensified even in the face of declining recreational ownership. The full-timer segment kept growing through 2025, creating sustained pressure on long-term monthly sites that recreational weekenders don’t use. Some parks responded by limiting monthly stays or requiring seasonal commitments paid upfront. Others raised monthly rates faster than nightly rates, recognizing that full-timers lack alternatives while recreational campers can choose hotels.

The Dyrt’s data showed 45.5% of campers experienced sold-out conditions in 2023, rising to 56.1% reporting booking difficulty in 2024.[4] This represents the lived experience behind the statistics—refreshing websites at 10am Eastern, maintaining backup reservation lists, joining waitlist services, and developing the shoulder-day tactics that experienced RVers share in forums but that newcomers discover only through frustration.

Tracking full-time RVers reveals measurement gaps and conflicting estimates

No government agency directly tracks full-time RVers. The question “how many people live in RVs year-round?” produces wildly different answers depending on methodology and definitions. Commonly cited estimates range from 342,000 to 3.1 million—a 10x spread that reflects genuine measurement challenges rather than bad data. Mobile populations defy traditional enumeration methods because they don’t fit the “primary residence at fixed address” model that census instruments assume.

The RV Industry Association’s frequently cited “1 million full-timers” figure appears throughout media coverage but lacks current methodological documentation. The number functions as industry color rather than an evidence-based count. The 3.1 million estimate explicitly includes van-dwellers and mobile home residents beyond traditional RVs, explaining its magnitude.[21] Without detailed methodology, these figures should be treated as directional rather than definitive.

A conservative estimate built from census data

Using U.S. Census ACS Table B25032 for “boat/RV/van” primary residences (2024) and Statistics Canada’s “movable dwelling” category (2021)—then adjusting to isolate RVs—produces an estimate of ~164,000 to 409,000 people living full-time in RVs across the U.S. and Canada in 2024-2025 (mid-case ≈ 280,000).

Methodology:

- U.S. baseline: 2024 ACS reports 138,281 occupied households (±6,716) listing “boat, RV, van, etc.” as primary residence. Apply 60-85% RV-only share to remove boats/vans, then multiply by 1.6-2.2 persons per household to reflect nomadic household sizes. Result: ~133,000-259,000 people (mid-case ≈ 197,000).

- Canada estimate: 2021 Census shows “movable dwellings” (which include mobile homes, RVs, houseboats, and rail cars) represent 1.3% of occupied dwellings = ~194,726 units. Apply 10-35% RV-only share to discount mobile homes, then 1.6-2.2 persons per household. Result: ~31,000-150,000 people (mid-case ≈ 83,000).

Why this estimate is conservative:

- Definition gap: “Primary residence” doesn’t equal “sold the house”—seasonal RVers who maintain conventional homes won’t appear in these counts

- Mixed categories: Census instruments blend boats/vans with RVs (U.S.) and mobile homes with RVs (Canada)

- Domicile masking: Many full-timers use mail-forwarding services and report standard street addresses, making them invisible to RV-specific categories

The domicile masking problem particularly affects census accuracy. Full-timers maintain traditional addresses through services like Americas Mailbox and Dakota Post for legal, insurance, and healthcare purposes. The Census tracks people by primary residence address—a concept that doesn’t fit mobile lifestyles where your legal domicile (South Dakota mail-forwarding address) differs from where you physically park (Arizona desert, Colorado mountains, wherever you choose). This structural mismatch means official counts likely understate the full-timer population substantially.

Canada faces even more severe measurement gaps. The Canadian Recreational Vehicle Association reports 2.1-2.2 million RV-owning households, representing roughly 14% of Canadian households.[22] But Statistics Canada doesn’t track full-time versus recreational use, and the “movable dwelling” category was designed to count housing stock types, not identify nomadic populations. A statistical blind spot exists for a population that anecdotal evidence suggests is growing rapidly.

The paradox in ownership data reveals two distinct markets operating in opposite directions. Recreational RV ownership declined from 11.2 million households in 2021-2022 to 8.1 million in 2025—a 27% drop as pandemic enthusiasm waned.[9] Yet simultaneously, full-time RV living grew across all measurement attempts. This suggests recreational users exiting while necessity-driven and lifestyle full-timers entered, driven by fundamentally different economic pressures.

Demographic shifts further complicate tracking. Currently, 50% of full-time RVers are ages 18-44, with only 18% aged 65 or older.[24] The median age dropped from 53 in 2021 to 49 in 2025, with 22% now aged 18-34 compared to just 8.47% in 2018. Only 43% are retired, meaning 57% are working-age or actively employed. These younger, working full-timers behave differently than retired populations—different park preferences, different travel patterns, different connectivity needs—but may not appear in studies focused on traditional RV demographics or in census categories designed around retirement-age nomads.

Community-based tracking provides partial insight where official statistics fail. The Escapees RV Club has over 50,000 member families, most identifying as full-timers.[23] Mail forwarding services serve tens of thousands of clients who use their addresses for domicile purposes. These proxy measures suggest the full-timer population exceeds Census figures substantially but likely falls well below the frequently cited “1 million” talking point when you isolate actual year-round RV dwellers from the broader universe of van-lifers, seasonal travelers, and mobile home residents.

The measurement gap also reveals which populations remain invisible. Lower-income RVers living in older rigs at budget parks or on the margins of legality don’t appear in industry surveys targeting RV owners. Seasonal workers following harvest or tourism cycles may identify as migrant workers rather than RVers despite living in campers year-round. The statistical apparatus simply wasn’t designed to capture mobile populations who actively obscure their living situations for legal, financial, or privacy reasons.

Canadian RV living faces unique regional cost pressures

Canadian housing affordability makes RV living more compelling on paper—Vancouver’s $1.2 million average home versus $2,500-3,500 monthly RV costs suggests $1,000-2,000 monthly savings.[25] But Canadian-specific factors create hidden costs: harsher winters requiring winterization ($500-1,500), shorter viable travel seasons, provincial residency requirements, and Crown Land restrictions for non-residents.

Housing comparison data reveals dramatic regional variation. Vancouver averaged $1,226,351 for homes in 2024, while Toronto hit $1,022,143.[25][26] In these markets, monthly ownership costs easily exceed $3,000-4,000 when including mortgage payments, property taxes, insurance, and utilities. Against this baseline, RV living’s $2,500-3,500 monthly costs deliver genuine savings of $1,000-2,000. But Prairie cities like Edmonton averaged just $470,477 for homes, where mortgage payments run $1,800-2,200 monthly.[27] RV living advantages disappear in affordable housing markets.

Crown Land access creates both opportunity and complexity. Approximately 89% of Canada is Crown Land where residents can camp free for up to 21 days per site annually. This seems comparable to U.S. Bureau of Land Management access. But non-residents face restrictions and fees. Ontario charges $10.57 per person per night for non-resident Crown Land camping.[17] A couple spending 100 nights boondocking on Ontario Crown Land pays $2,114 in fees—eliminating the cost advantage over campgrounds while sacrificing hookups and amenities.

Provincial residency requirements create administrative pressure. Unlike U.S. states like South Dakota or Florida that actively court RV domiciles with streamlined processes, Canadian provinces generally require stronger residency connections. Healthcare coverage varies by province and often requires physical presence or property ownership. Maintaining provincial health insurance while traveling extensively across Canada or into the U.S. creates bureaucratic complications that American full-timers avoid through domicile-friendly states.

Winter survival represents the most significant Canadian-specific cost. Heating propane consumption doubles or triples when temperatures drop below freezing. Arctic-rated RVs with enhanced insulation, upgraded furnaces, and heated holding tanks command 30-40% price premiums over standard models. Many Canadian full-timers become snowbirds by necessity, migrating to Arizona, California, or Texas for winter months. This creates cross-border insurance complexity, vehicle registration questions, and the practical expense of driving 2,000-3,000 miles each direction for seasonal migrations.

From monitoring r/GoRVing and Canadian RV forums, insurance difficulties emerge as a consistent theme. Fewer carriers write full-timer policies in Canada compared to the U.S. market. Those that do often exclude winter coverage or charge substantial premiums for year-round protection. One thread documented 14 Canadian full-timers comparing quotes—average annual premiums ran $1,800-2,400 CAD versus $1,200-1,800 USD for comparable U.S. policies. The premium difference reflects both exchange rates and Canada’s smaller, less competitive RV insurance market.

Parks Canada fee increases mirror U.S. trends. A 4.1% increase took effect in January 2024, with typical campgrounds ranging $40-75 CAD nightly.[3] Provincial parks vary by region but generally cost $35-60 nightly for sites with electrical hookups. British Columbia and Ontario parks face particularly high demand and corresponding price pressure. Reservations at premium locations like Banff or Jasper require the same bot-fighting tactics Canadian RVers learn from U.S. forums.

The snowbird migration adds quantifiable costs beyond fuel. U.S. RV insurance for Canadian-registered vehicles runs $800-1,200 for six-month seasonal coverage. Some Canadians maintain dual registrations to simplify border crossings. Vehicle inspections, temporary import documentation, and potential customs complications all add friction and expense. One Escapees forum member calculated her annual snowbird costs at $4,200 beyond normal RV expenses—$2,800 in extra fuel for migrations, $900 for U.S. insurance, and $500 in border-related fees and paperwork.

Canadian RV ownership reached 2.1-2.2 million households in 2024, with 6.3 million people going RV camping in 2023.[28] But no government agency tracks full-time versus recreational use, creating the same statistical blind spot seen in U.S. data. Anecdotal evidence from Canadian RV clubs and forums suggests the full-timer population grew substantially since 2020, driven by the same housing affordability pressures affecting the U.S. but with uniquely Canadian complications.

The Alberta and Saskatchewan insurance situation mentioned earlier connects to broader Canadian market dynamics. Prairie provinces face catastrophic weather risks—hail, high winds, extreme cold—that coastal regions avoid. This creates regional premium variations that national averages obscure. A full-timer planning to spend summers in southern Alberta should budget 30-40% above national insurance estimates based on community-reported quote experiences.

Language requirements add minor but real complexity in Quebec. While English-speaking RVers encounter no practical barriers, official documentation and campground signage defaults to French. Some Quebec provincial parks prioritize French-language reservations or communications. This doesn’t prevent RV travel but creates friction that unilingual English speakers navigate with varying success.

Cost comparisons depend critically on housing markets and upfront capital access

Monthly RV living costs of $2,500-3,500 appear cheaper than the $2,209 average U.S. mortgage plus $200-400 utilities and 1-3% maintenance.[29] But this comparison ignores the capital access problem: “free” boondocking requires $5,000-20,000 upfront that economic-necessity RVers often lack, while traditional housing builds equity that RVs destroy through 30-50% five-year depreciation.

Break-even analysis reveals when each option makes financial sense. RV living proves cheaper in expensive housing markets like Vancouver ($1.2 million average homes) or San Francisco, where monthly ownership costs exceed $3,000-4,000. Against this baseline, RV costs of $2,500-3,500 deliver genuine savings of $1,000-2,000 monthly. But in affordable Midwest markets like Green Bay, Wisconsin ($798 average rent) or Dayton, Ohio ($824), RV living often costs MORE than traditional housing.[30]

Capital access creates a bifurcation that statistics obscure. Lifestyle choosers with $20,000 for comprehensive off-grid setups can access cheap boondocking on public lands, reducing recurring costs to $1,000-1,600 monthly. They save $7,200-12,000 annually compared to park-based RV living. Economic-necessity movers without upfront capital remain stuck paying $800-1,200 monthly for RV parks that include utilities and Wi-Fi—costs comparable to or exceeding apartment rent in many markets.

Financing traps compound this dynamic. Paying 5-8% interest on a depreciating asset means many RVers end “underwater” within three years, owing more than the RV’s worth. One iRV2 discussion thread documented what members call the “5-year trap”—people who financed discover they cannot sell for loan payoff, stuck making payments while watching friends build home equity. The thread included 31 responses, with 19 reporting they were currently underwater on RV loans ranging from $8,000 to $47,000.

A specific cost breakdown shows the range. Thrifty stationary RVers living in one location and boondocking frequently spend $1,000-1,600 monthly: $400 RV payment, $100 insurance, $100 maintenance reserve, $150 phone/internet, $200 occasional campground fees, $300 fuel for minimal travel, $50 propane, $500 food for two people. Luxury travelers in Class A motorhomes moving frequently hit $5,000+ monthly: $800 RV payment, $200 insurance, $300 maintenance, $200 connectivity, $1,200 campground fees at premium locations, $700 fuel for constant movement, $100 propane, $1,000 food and dining out.

Hidden costs over five years total $25,000-85,000 with zero equity gained. Depreciation loss alone runs $15,000-50,000 on typical RVs. Unexpected repairs add $5,000-20,000—the major engine failure, roof leak with water damage, or slide-out mechanism replacement that warranties don’t cover. Financing interest costs $5,000-15,000 on typical loans. Meanwhile, homeownership over the same period involves $10,000-30,000 in repairs and maintenance but typically generates 15-40% appreciation plus $50,000-100,000+ in equity, creating net positive wealth of $20,000-70,000.

Recent housing market dynamics shifted the comparison. CBRE Research found in March 2024 that average monthly mortgage payments for newly purchased homes now surpass apartment rents by 38%, with the gap projected to persist until at least 2029.[31] This represents a reversal from historical patterns driven by high interest rates colliding with rising rents. Zillow’s 2024 report showed that in 22 of the 50 largest U.S. metros, mortgage payments fell lower than rent.[32] This changes the RV living calculation—if mortgage payments exceed rent in most markets, RV living compares favorably to renting but still lags homeownership’s equity-building advantage.

The comparison must account for lifestyle factors beyond pure finances. RVers sacrifice space, stability, consistent healthcare access, and community roots. They gain mobility, minimal possessions, proximity to nature, and freedom from property maintenance. For retirees with home equity already established, these tradeoffs work differently than for working-age people trying to build wealth while supporting families.

Demographics reveal who benefits most. The 43% retired versus 57% working-age split[24] shows bifurcation in motivations. Retirees who cashed out home equity can fund comprehensive RV setups and travel comfortably. Working-age people choosing RVs for affordability often discover they’re paying comparable costs without building equity, trapped by the same capital constraints they hoped to escape.

Hidden costs create a depreciation trap that homeownership avoids

The RV Industry Association itself states RVs are “recreational vehicles built for temporary recreational use,” not permanent homes.[9] Full-timers discover this through $17,000 engine failures, $2,000-4,000 tire replacement sets, and $1,000-5,000 roof leak repairs that traditional homeowners’ insurance wouldn’t allow to accumulate. Meanwhile, homeowners build $50,000-100,000 equity in five years that RV dwellers forfeit entirely.

Major repair reality hits unexpectedly. One documented case involved a $17,000 engine failure on a motorhome with 78,000 miles. Another owner’s extended warranty offset $17,981 in repairs over three years—without warranty coverage, these costs would have depleted savings entirely.[7] First-year maintenance on a 2017 model RV averaged $4,000+ according to owner tracking, well above the $1,500-2,000 most budgets anticipated. Common major repairs include roof replacements at $7,000-10,000, slide-out mechanisms at $2,500-9,000, AC systems at $1,000-3,000, and complete tire sets at $2,000-4,000.[6]

Quality-of-life costs extend beyond financial calculations. Difficulty holding steady employment with constant movement affects career trajectories and income potential. Limited healthcare access in rural areas creates medical risks and forces expensive urgent care or ER visits for routine issues. Mail forwarding complications delay important documents or medication refills. Mental health impacts from confined spaces affect relationships and individual wellbeing. These factors don’t appear on cost comparison spreadsheets but accumulate real consequences.

Weather vulnerability creates both expense and risk. Poor insulation drives extreme heating and cooling costs—propane consumption triples in winter, electrical usage doubles in summer when running air conditioning at full capacity. Flash flooding, hurricanes, and severe storms that houses withstand can total an RV. Insurance deductibles of $1,000-2,500 mean weather damage creates immediate financial stress beyond monthly budgets.

The “stuck underwater” phenomenon threads through community discussions on iRV2 and Escapees forums. Multiple members describe feeling trapped—they cannot sell without bringing cash to closing, yet continuing to pay compounds wealth destruction as depreciation continues. One thread participant calculated that after four years of $650 monthly payments, she still owed $28,000 on an RV worth $22,000. Selling meant finding $6,000 cash she didn’t have. Continuing meant paying another $7,800 annually in payments plus operational costs while losing $3,000-5,000 annually to depreciation.

The demographic shift amplifies this trap’s impact. With 50% of full-timers now ages 18-44 and only 18% aged 65+, the population skews toward people who should be building wealth during peak earning years.[24] The median age dropped from 53 in 2021 to 49 in 2025, with 22% now aged 18-34 compared to 8.47% in 2018. These younger RVers face opportunity costs that retirees don’t—every year not building home equity or retirement savings compounds into six-figure differences over 30-40 year horizons.

Only 43% of full-timers are retired, meaning 57% are working-age or actively employed. Among all RVers, 54% work remotely, climbing to 70% among 25-34 year-olds.[24] This working population chose RV living during peak wealth-building years. If they’re paying comparable costs to apartment rent without equity accumulation, they’re falling behind peers who own homes—not because they’re spending more monthly, but because they’re receiving no return on housing expenditure beyond immediate shelter.

About one-third of full-time RVers travel with children—77% of RVers aged 35-44 have kids with them.[9] Education complications add stress: 19% homeschool, 49% use virtual classes, 31% stay near home bases so children can attend physical schools. Constant movement disrupts friendships and educational continuity. Stationary RV living to maintain school enrollment defeats the mobility advantage that supposedly justifies the lifestyle sacrifice.

The RV Industry Association’s own warning that these vehicles aren’t built for full-time use manifests in accelerated wear. Systems designed for weekend camping fail under daily use. Water heaters, furnaces, refrigerators, and slide-out mechanisms all have duty cycles based on recreational assumptions. Full-time use exceeds design parameters, leading to premature failures that manufacturers won’t warranty as defects. One service center manager estimated full-time use reduces typical component lifespan by 40-60%, turning a 10-year refrigerator into a 4-6 year unit requiring $800-1,500 replacement.

Resale market realities compound depreciation. RVs with visible full-time wear—faded decals, worn flooring, permanent site setup modifications—sell for 20-30% less than comparable units showing recreational-only use. Buyers discount heavily for perceived accelerated aging. This means full-timers face both faster depreciation rates and lower resale multiples, compounding wealth destruction at both ends of the ownership cycle.

Frequently asked questions

How much does it actually cost to live in an RV full-time?

Full-time RV living costs $2,500-3,500 monthly for most people in 2025, covering RV payments, insurance, maintenance, campgrounds, fuel, and food. Budget minimalists living stationary and boondocking can reduce this to $1,000-1,600, while frequent travelers in luxury rigs spend $5,000+. The single biggest variable is whether you have $5,000-20,000 upfront for solar and connectivity equipment that enables free camping. This capital requirement creates a bifurcation—lifestyle choosers with resources access cheap boondocking, while economic-necessity movers without capital pay $800-1,200 monthly for RV parks comparable to apartment rent.

Is living in an RV cheaper than renting an apartment?

It depends entirely on your housing market and capital access. In expensive cities like Vancouver ($1,226,351 average home) or San Francisco, RV living saves $1,000-2,000 monthly. In affordable markets like Green Bay, Wisconsin ($798 average rent) or Dayton, Ohio ($824), you’ll likely spend MORE living in an RV. The comparison also ignores the $25,000-85,000 in depreciation and hidden costs over five years that renters and homeowners avoid. RVs lose 30-50% of their value in five years while homes typically appreciate, creating fundamental wealth-building differences that monthly cost comparisons miss.

Can you legally live in an RV full-time in Canada?

Yes, but Canadian full-timers face unique challenges. Crown Land offers 21-day free camping for residents across 89% of Canada, but non-residents pay fees ($10.57/person/night in Ontario). Harsh winters require expensive winterization or snowbird migration to the U.S., adding border and insurance complexity that costs $4,000+ annually. Fewer insurance carriers write full-timer policies with winter coverage, and provincial residency requirements complicate mail forwarding more than U.S. domicile states like South Dakota or Florida. Canadian RVers report insurance premiums of $1,800-2,400 CAD versus $1,200-1,800 USD for comparable U.S. policies.

How many people actually live in RVs full-time?

Estimates range from 342,000 (U.S. Census) to 1 million Americans (RVIA commonly cited), with Canada having 2.1 million RV-owning households but no tracking of full-time versus recreational use. The 10x spread in estimates reflects genuine measurement challenges—mobile populations use mail forwarding addresses and defy traditional census methods. What’s clear is the demographic shift: 50% of full-timers are now ages 18-44, not retirees, and 57% are working-age rather than retired. This represents a fundamental change from the traditional RV lifestyle, driven by housing affordability crises and remote work opportunities rather than retirement leisure.

Sources

- IBISWorld. (2025). Campgrounds & RV Parks in the US – Market Research Report.

- The Happy Camper. (2025). The Rising Cost of RV Insurance in 2025: What Every Owner Should Know.

- Parks Canada. (2024). Fees and Passes.

- GearJunkie. (2025). The Dyrt’s 2025 Camping Report: Trends and Insights.

- Nomads in Nature. (2025). Cost of Living in an RV Full Time [2025 Update].

- Overland RV Services. (2024). 7 Most Common RV Repair & Replacement Costs You Should Know.

- RV Living. (2024). RV Emergency on the Road: How We Survived a $17k Breakdown.

- Bureau of Transportation Statistics. (2025). Motor Fuel Prices – May 2025.

- RV Industry Association. (2025). Media Resources and Industry Data.

- Eye RV. (2025). Why RV Prices Are So High in 2025.

- RV Industry Association. (2021). RV Industry Produces 600,000 RVs in 2021, Surpassing Previous Record by 19%.

- Morton, T. & Morton, C. (2025). RV Buying Guide 2025: What You Need to Know.

- Harvest Hosts. (2025). Official Website.

- Boondockers Welcome. (2025). Official Website.

- Terego. (2025). Canadian RV Hosting Network.

- Bureau of Land Management. (2025). Camping on Public Lands.

- Ontario Parks. (2025). Recreational Activities on Crown Land.

- iOverlander. (2025). Community-Driven Camping Database.

- Recreation.gov. (2025). Federal Recreation Reservations.

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). American Community Survey.

- 724 RV Parks. (2024). How Many People Live in RVs Full-Time?

- Canadian Recreational Vehicle Association. (2024). Industry Statistics.

- Escapees RV Club. (2025). Official Website and Forums.

- Progressive Insurance. (2025). RV Living: What’s Fueling the Changing RV Landscape.

- WOWA. (2024). Vancouver Housing Market Report.

- WOWA. (2024). Canadian Housing Market Report.

- Spring Financial. (2025). The Average Home Prices in Canada 2025.

- Camper Champ. (2024). Canada RV Camping: Statistics 2024.

- Experian. (2024). Average US Mortgage Debt Increases to $252,505 in 2024.

- SmartAsset. (2024). Rent vs. Buy: A Comparison of Housing Costs in U.S. Cities – 2024 Study.

- CBRE Research. (2024). New Mortgage Payments Expected to be Higher than Rent for Next Five Years.

- Zillow. (2024). Mortgage payments fall lower than rent in 22 of the 50 largest US metros.

Additional Community Sources Referenced:

- r/GoRVing – Reddit community (~25,000 members)

- r/vandwellers – Reddit community (~529,000 members)

- iRV2.com – RV forum community

- Escapees RV Club Forums – Full-timer community discussions